Yield Is Not Return

Higher Yields Mean Higher Losses

By: Greg Obenshain

In our recent piece, What Does a Yield Buy?, we suggested that the yield on the BB index, currently 6.6%, is a better indicator of the potential return of the high-yield market than the yield of the market itself, currently 7.8%. Why? Because, while the BB market tends to come close to earning its yield, the lower-rated portions of the market, the B and CCC segments, tend to underperform their yields and have historically delivered returns slightly below that of the BB segment.

But why do lower-rated bonds underperform their yields? One way to understand what is going on is to look at the price returns of the bonds in each rating segment. This is the return without interest payments. If all bonds paid off at par, we’d expect this return to be zero. Price returns could theoretically be positive if bonds leave the rating segment at higher prices due to upgrades or because they are called early above par. Price returns will be negative if they leave the rating segment at lower prices due to downgrades or because they default. Below is the history of price returns by rating.

Figure 1: Annualized Price Returns by Rating Index, December 1986 – January 2024

Source: Bloomberg. Uses intermediate high-yield (1-10 year) indices.

In our opinion, the story is clear. B and CCC bonds lose returns to price losses. And this is consistent with long-term data from Moody’s 2022 annual default study, which showed that, from 1983 to 2022, 32% of CCC and 20% of B debt defaulted over five years while just 8% of BB debt and 2% of BBB debt defaulted over the same period.

It’s also informative to look at the price indices over time. Below we show the history of the price indices.

Figure 2: Annualized Price Returns by Rating Index, December 1986 – January 2024

Source: Bloomberg. Uses intermediate high-yield (1-10 year) indices.

As shown above, high-yield bonds are clearly pro-cyclical, but, while BB bonds tend to recover their price losses, B and CCC bonds do not reclaim their previous levels.

In fact, negative price returns are more damaging to expected returns than may be apparent. B and CCC bonds often trade at a discount to par, and that discount is included in the yield calculation. Currently, the Bloomberg CCC intermediate (1-10 year) index has an average price of 81, and the B index has an average price of 95. When yields assume a pull to par and the price goes down instead, that increases underperformance relative to yield.

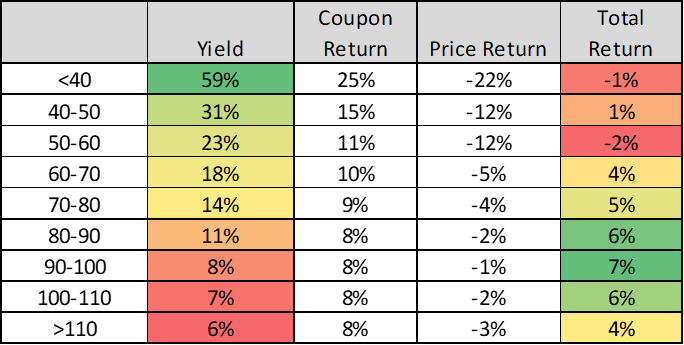

This leads to another surprising result. Discounted bonds often look attractive because they have high yields and there is a belief that they should pull to par. But that is not the result, on average. If you bucket high-yield bonds by their price and look at the returns, you get the following result.

Figure 3: Returns by Bond Price, January 1997 – January 2024

Source: Verdad Bond Database, Verdad Analysis. High-yield bonds only.

Increased losses fully offset the promise of higher yields. Again, it appears the best you can do is to capture the yield of the performing bonds. This speaks volumes about how to think about high yield. There is nothing wrong with chasing high yields so long as you also price in an expected loss, but we believe it is often more profitable to accept a yield that is more likely to be realized rather than to chase higher yields that are likely to come with offsetting price losses.

In some ways, the fact that BB, B, and CCC bonds all return about the same despite very different yields points to remarkable efficiency in the market. Investors have somehow priced bonds to compensate for default risk such that returns across all ratings categories approximately even out. A generous interpretation is that investors are savvy and rationally pay up for bonds with higher potential returns, accepting higher risk for higher potential return. A less generous interpretation is that investors are greedy and gravitate toward higher yields that are attractive in the moment and less attractive over time. We gravitate toward the second explanation for a simple reason. Just imagine you are an analyst at a big fund. Do you make your name pitching the low-yielding bond or the high-yielding bond? Now imagine you are the PM marketing the fund. Do you want to market a fund with a higher or lower yield?

We believe this story is playing out in private credit right now, where the marketed yields have been very attractive. Much of private credit is highly levered private equity deals where loans are very much of similar quality to the B and CCC debt that has historically defaulted at high rates. Just because private credit isn’t rated doesn’t mean its risk is magically reduced. This does not mean that these are unprofitable deals, but it does make it likely that returns will fall below marketed yields. Over the history of our internal bond dataset, returns for bonds rated single B have been 3% behind their yields, and returns for bonds rated CCC have been 7% behind their yields. We suspect that the average result for highly levered private credit deals will fall within that range.

We believe that, in high-yield, the winning strategies have lower yields. You don’t want a portfolio that yields more than the high-yield index. But it is far easier to sell strategies with high yields, and it is far more fun to pitch bonds with higher potential returns. For this reason, we suspect that yield chasing with mediocre results is here to stay.