Risky Banks

Financially stable banks are essential to the functioning of our economy. But regulators and investors alike have struggled to find a good way to distinguish which banks pose the highest economic risk. Existing methodologies, like the Basel convention’s “risk-weighted asset” calculations, are deeply flawed and have historically lacked predictive power.

But in a groundbreaking new paper, Stanford professor Charles Lee (a friend and mentor) has developed an innovative methodology for assessing bank risk. Lee’s measure of “loan portfolio risk” predicts expected loan losses and is effective at predicting bank failures up to five years in advance.

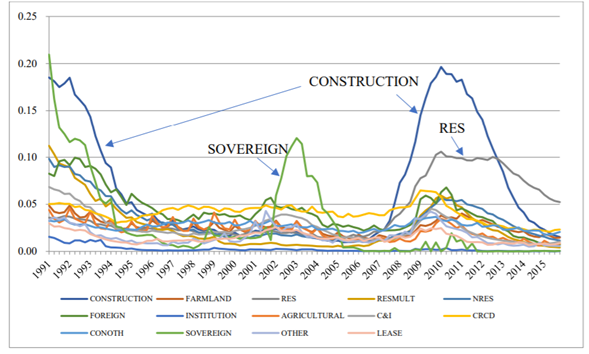

The most dangerous types of loans are those with the most variable default rates. These types of loans can look benign for long periods but then experience massive default waves that catch banks by surprise and thus lead to failures. Lee finds that residential real estate loans, construction loans, and—surprisingly—sovereign loans have the highest standard deviation of defaults.

Figure 1: Aggregate Delinquency Rates by Loan Type over Time

Source: Lee et al.

Greater exposure to these higher risk loans creates a higher risk of failure.

But that’s only part of the story. It’s not just the exposure to risky loans but the correlation of the defaults of those risky loans that matters. A bank could own multiple categories of highly risky loans, but if those types of loans had uncorrelated default rates, the bank’s loan portfolio might not actually be that risky.

We know, for example, that construction loans and residential real estate loans are two of the riskiest categories. But those two categories have a correlation of only 66%, whereas construction has an 86% correlation with non-residential real estate. In other words, if we posited two banks making the same total amount of loans, the bank that makes loans in construction and non-residential real estate would be riskier than the bank that makes loans in construction and residential real estate. The correlation matrix for the five largest loan categories is below.

Figure 2: Correlations of Aggregate Delinquency Rates across Loan Categories

Source: Lee et al.

These two factors—the types of loans a bank makes and the correlation of loan default rates by type—are both important to predicting future bank failures, with the type of loan being a bit more important than the correlation of loan defaults.

When combined into Lee’s “loan portfolio risk” score, these variables are powerfully predictive of future bank failures, significantly outperforming existing techniques. On a five-year horizon, the score is 53% accurate in predicting failure versus the commonly used CAMELS score, which achieves 41% accuracy on a five-year horizon.

This formula also has predictive power for the stock price performance of banks. During the financial crisis period (2007–2011), banks that scored in the lowest risk decile of Lee’s risk score earned 40.2% higher average annualized returns than the firms in the highest risk decile, as the majority of the firms in the highest risk decile failed and those in the lowest risk decile sailed along with almost no failures.

Understanding the causes and predictors of bank failures is very important to financial stability, and Lee’s latest work offers a dramatic improvement over the current “risk-weighted assets” calculations popularized by the Basel convention and the CAMELS score used by many regulators. This portfolio-based approach to understanding banks is also exploitable in equity markets, which do not fully price in this view of bank risk.