Contrarian Investing in Commodity Cyclicals

Some of the best private equity deals of all time have involved leveraged bets on wildly volatile and unpredictable commodity cyclicals.

Blackstone’s $640M investment in chemicals manufacturer Celanese caught the bottom of a downturn in the chemicals market. Just after the deal closed, industry capacity utilization turned up and the company’s volumes soared 15% after several consecutive years of decline. Blackstone sold the company nine months later for about four times the original price.

A consortium of some of the biggest names in private equity, including KKR and Texas Pacific Group, saw similar rapid profits in their 2004 investment in a group of powerplants they called Texas Genco. Soon after the deal closed, there was a 100%+ surge in natural gas prices, and the PE consortium was able to sell the company in less than a year to NRG Energy for more than 6 times the original transaction price—one of the best private equity deals of all time.

Private equity deals in volatile commodity industries might not be a big part of the marketing story sold to LPs, but the reality is that some of PE’s greatest successes have been in the metals and mining, chemicals, and energy sectors. What these sectors have in common is big price swings that can drive massive increases in profit without new investment—a key distinction given that the debt from the leveraged buyout constrains new investment spend and thus puts a damper on investment-fueled growth in many cases.

Can public market investors profit from these same dynamics? And how much does timing the end of the market cycle matter to equity returns?

We conducted an anecdotal study of a few major cyclical companies in a few major cyclical industries to better understand the dynamics at play. While distinctly unscientific, this initial examination reveals some interesting findings about how to profit in cyclical industries.

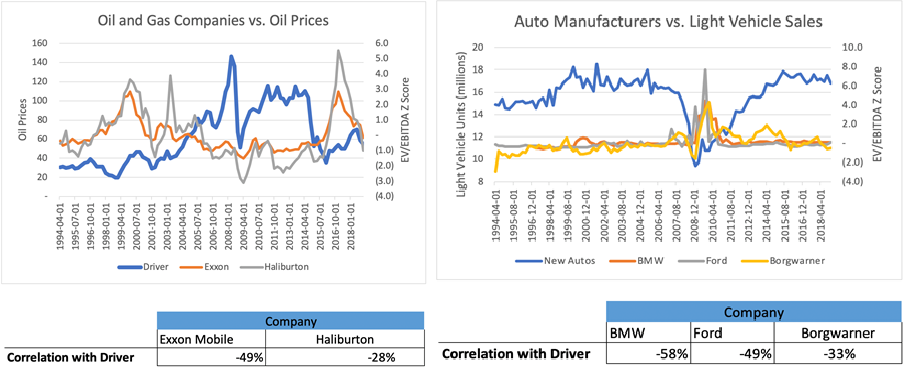

We used 25 years of quarterly economic data from FRED to describe variations in the underlying conditions of a few chosen industries: oil and gas, construction, chemicals, and auto. We looked at companies with long operating histories in each sector and compared stock price returns and trading multiples to measures of economic activity for each industry.

We found first that markets price in the cyclicality, with these companies trading at low multiples at peak cycle and high multiples at cycle troughs. There is a strong inverse relationship (ranging from a -28% correlation to a -80% correlation) between EV/EBITDA multiples and industry economic data.

Figure 1: Firm EV/EBITDA Multiples vs. Measures of Economic Activity over Time

Source: FRED, Capital IQ, Verdad Research

For example, when oil prices were below $37 a barrel (bottom quartile), Exxon traded at an average multiple of 8.2x, but when oil prices were above $88, Exxon’s EBITDA multiple fell to an average of 5.7x. Similarly, when the number of new homes under construction was below 772,000 (bottom quartile) DR Horton and Lennar traded at average multiples of 21.7x and 34.5x, but they reverted to 8.1x and 9.4x respectively when the number of new homes under construction surpassed 1,072,000 (top quartile).

These results suggest some market efficiency and anticipation of mean reversion. The data show that as measures of economic activity reach historic lows, investors purchase affected companies. Expecting that these economic data will revert to their historic averages, positions in these companies become crowded and multiples become incongruent with concurrent fundamentals.

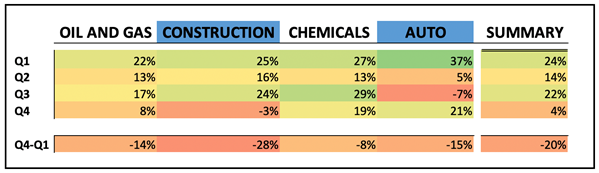

But this mean reversion is not fully priced in. Despite the inverse correlation of trading multiples, forward annual returns for companies at cycle-bottom exceed those at cycle-top by 20% on average. Figure 2 shows forward annual returns are still greatest in the lowest quartile of economic activity.

Figure 2: Industry Annual Forward Returns Relative to Economic Activity

Source: FRED, Capital IQ, Verdad Research

Investors who are willing to buy in at cycle troughs, even when they pay higher multiples for these cyclically low earnings, tend to earn attractive returns.

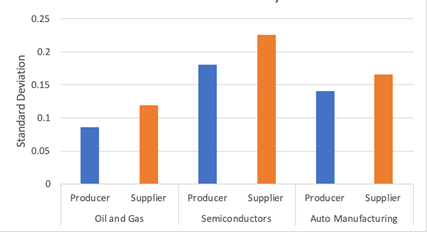

We also found evidence of a bullwhip effect in industry supply chains. Figure 3 compares the standard deviation of changes in quarterly share prices for producers and suppliers within the oil and gas, semiconductor, and auto manufacturing industries.

Figure 3: Volatility of Quarterly Price Movements in Cyclical Industries

Source: FRED, Capital IQ, Verdad Research

On average, changes in supplier share prices are 27% more volatile than changes in producer share prices within these industries. These data suggest that changes in an industry economic activity are amplified down the supply chain. For investors looking to take on even more risk in cyclical industries, companies further down the supply-chain bullwhip represent an attractive opportunity.

Over the past 10 years, cyclical industries have largely underperformed the market. Figure 4 shows performance of cyclical industries and the S&P 500 over time. With the exception of the homebuilding industry, companies in cyclical industries have considerably underperformed those in the S&P 500. The metals and mining industry and the energy industry have performed particularly poorly, generating near-zero or negative returns for investors.

Figure 4: Cyclical Industry Returns vs. S&P 500 over Time

Source: FRED, Capital IQ, Verdad Research

While investing in cyclical industries ten years ago would have been a poor decision, our research suggests some opportunities may exist today. The economic activity measures for the semiconductor industry and independent power producers are near historic lows (bottom quartile). Meanwhile, the measure for construction is near its historic high (in the top quartile).

Some investors avoid these cyclical industries because of their wild and unpredictable fluctuations, but these data suggest that using economic data to evaluate investment opportunities in cyclicals and buying at economic troughs can provide above-market returns. Cyclicals may be volatile and unloved, but private equity firms have shown that there’s significant profit to be had if those price swings move in the right direction.