A Whale of a Tail: The Bank of Japan's ETF Hoard

Part I: A case study on the impact of correlated ETF fund flows on stock price movements and what seems to have happened when the decade-long trend stopped.

By: Verdad Research & Sho Miyazaki

The efficient markets hypothesis fully allows for the presence of correlated trading strategies and irrational actors by assuming that any correlated and irrational trading should be arbitraged if there are at least some rational actors left in the market. Or, to put it in the context of this article’s topic: “If the Bank of Japan wasn’t buying that stuff, somebody else would,” as one Tokyo hedge fund manager told us in Roppongi Hills back in 2017.

But even Eugene Fama called it quits when trying to defend price perfection in the presence of a government whale:

Journalist: But Fannie and Freddie’s purchases of subprime mortgages were pretty small compared to the market as a whole, perhaps twenty or thirty per cent.

Eugene Fama: (Laughs) Well, what does it take?

What does it take? Historically, it’s been nearly impossible to answer this question given an array of analytic challenges: how to aggregate the quantum and connection of correlated fund flows, accurately classify any non-market incentives behind them, and test the exact buying patterns to see the price impact on the exact target supplies of individual assets.

But the Bank of Japan’s massive intervention in the Japanese stock market offers us a chance to try to answer Fama’s question and, in the process, better understand how central banks can impact markets at the extremes.

Japan’s stock buying program is remarkable both for its magnitude and for the availability of precise data. The BOJ’s balance sheet of ETF holdings hit $450 billion this year, which is about 7% of all public stock value in Japan. And we have 10 years of daily trading data, with the BOJ telling us exactly the amounts and end stocks they were purchasing every day under exact ETF construction rules, all while confirming that the intentions behind each yen of their fund flows were not price arbitrage.

The question is particularly interesting right now because, over the last 1.5 years, the BOJ ramped the program to unprecedented levels during COVID before bringing it to a screeching halt of near zero purchases in 2021. These dynamic moves at the end of a long-term purchasing pattern may help shed some light on the impact of the whale’s tail and on how to answer Fama’s question.

Background on the Bank and Program

Unlike the Bank of America, the Bank of Japan is the central bank of its nation. And unlike BoA, BOJ did not pay $16.7 billion in settlements for alleged financial fraud in the 2008 crisis. Instead, like most all central banks, the Bank of Japan can legally steal money from retirement accounts by pursuing their mandate to increase inflation and depreciate the national monetary base. And while they have been hard at work at this public service, the Bank of Japan had been notoriously unsuccessful for years, struggling to hit their 2% inflation target.

The ETF purchase program was just one plank among the many aggressive quantitative and qualitative easing measures the Japanese pioneered, including the zero interest rate policy and the highly innovative redirection of COVID relief funds to giant squid statues.

The ETF program started small in 2010, after 20 “lost years” coming out of the 1989 asset bubble. Back then, the original stated purpose of the $4.5 billion program was to “encourage the decline in risk premiums.” But the ETF policy was put on steroids under Abenomics (up to $120 billion per year) with a kicker of human growth hormone during the COVID crisis. After the COVID crisis, the bank abruptly stopped buying in 2021 for the first time, making for some interesting shifts in the demand curve for stocks.

After what looks like the end of a decade-long buying spree of epic proportions that only accelerated until 2021, we can now begin to take stock of the Bank’s long-term impact on stocks.

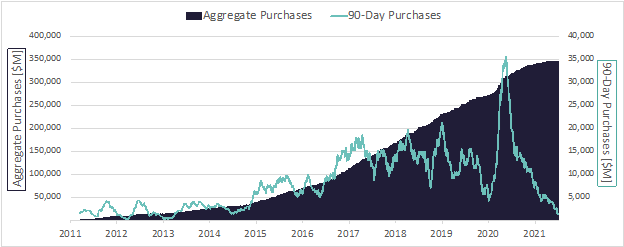

Below is the growth of the program over time, showing the aggregate amount of BOJ ETF purchases and the trailing 90-day purchase amount.

Figure 1: Scale of BOJ ETF Purchases and Aggregate Holdings

Source: BOJ

The BOJ telegraphs exactly what they are buying. Originally the BOJ bought ETFs tracking the Nikkei 225 index (a price-weighted index tracking 225 stocks) and has since transitioned to purchasing only the TOPIX index (a free-float weighted index tracking all 2000+ stocks on the Tokyo Stock Exchange).

When selecting the Nikkei 225 early on, the BOJ was apparently not concerned with dumping billions of dollars into an index that was weighted based on per-share prices rather than market-cap weighting, meaning 10% of every dollar went to Fast Retailing Co (aka Uniqlo at 76,000 yen per share and $19B in revenue) but only 0.07% of every dollar went to Nissan Motor Corp (only 560 yen per share but $71B in revenue). But after eight years of scholarly research, in August of 2018 the BOJ shifted to the TOPIX index as the main target and the only target since April 2021.

Scholars had observed the distortionary effect of large-scale asset purchase through price-weighted indexes. Barbon and Gianinazzi (2019) claim that the “purchases of ETFs tracking the price-weighted Nikkei 225 index generate significant pricing distortions relative to a value-weighted benchmark.” Moreover, Harada and Okimoto (2019) found that “the cumulative treatment effects on the Nikkei 225 are around 20% as of October 2017” and “the BOJ’s interventions have had considerable impacts on the market.”[1]

Looking for distortions in the price-weighted Nikkei 225 buying seemed like low-hanging fruit, given the Uniqlo versus Nissan disparity. However, it is often assumed that the shift to the market cap-weighted TOPIX index solved the price distortion issues, as pointed out in much of the early literature, because every dollar invested in the TOPIX ETF is spread out in proportion to the relative size of each company as measured by free-float market capitalization. This should dramatically mitigate overbuying of individual securities.

But if it didn’t, this would be very interesting, not just for the BOJ program, but for ETF fund flows in general, which are often hard to aggregate. Developed equity markets are majority passive now after a dramatic decade of increases, and free-float cap-weighted indexes are the norm, whether it’s Nomura’s TOPIX ETF or the S&P 500 ETFs offered by Vanguard or Blackrock.

In next week’s weekly research, we will explore what we found by analyzing this data and discuss the implications for other markets where government intervention and passive fund flows are becoming more prominent.

Acknowledgement: Coauthor and summer intern Sho Miyazaki is a rising junior studying political science at Keio University in Tokyo, where he also works as a performance data analyst of the varsity rugby team. After studying at Harvard College as a visiting student, he is now actively seeking career opportunities in finance and data science. Please reach out to us if you would like to connect with Sho.

[1] Apart from the Nikkei 225 price distortions, more recent literature has found additional problems with the BOJ’s ETF program that are outside the scope of this paper. See Charoenwong et al. (2020) on weak corporate governance and capital inefficiency.