Total Concentration

As “virtue is proved by its contrary,” so too are the benefits of diversification proven by the costs of hyper-concentration.

By: Brian Chingono

There is a belief among many investors, including prominent stars like Warren Buffett, that diversification “makes very little sense for anyone who knows what they are doing.” Some even go as far as to advocate for hyper-concentration, based on Buffett’s view that “if you find three wonderful businesses in your life, you’ll get very rich. And if you understand them, bad things aren’t going to happen to those three.”

On the other hand, Nobel Prizes have been awarded to financial economists whose research insights were based on diversified portfolios of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of stocks. In addition to contributing to our understanding of how financial markets function, these economists have made their mark on Wall Street. Multitrillion-dollar investment firms like Vanguard and BlackRock have been built upon their research, compounding wealth for millions of investors along the way.

So it seems we have competing truth claims. Either diversification is “di-worsification” that should only be practiced by the ignorant, or it is a “free lunch” that improves investment outcomes without increasing risk, as claimed by the academics. It cannot be both.

We set out to evaluate these competing truth claims in the context of equity investing by comparing the best arguments for concentration against the evidence from decades of empirical data.

The most forceful arguments for hyper-concentration, as articulated by the investment process consultant Alpha Theory in their Concentration Manifesto, fall along three lines:

Conviction: Any manager who has a decent system for security selection should have a sense that more attractive stocks have higher expected returns than less attractive stocks. Therefore, according to this line of reasoning, managers should simply concentrate their holdings in a handful of their most attractive stocks, where they have highest conviction for generating outperformance.

Mental capital: Every portfolio manager has a limited amount of time to allocate toward researching and understanding their holdings. Since each additional holding spreads a PM’s time more thinly, it is better to have fewer holdings so that the PM can properly understand every investment in their portfolio.

Diversification is for allocators: Managers who know their investments well should focus solely on maximizing expected returns and leave risk-management to allocators, who can diversify across multiple concentrated managers. According to this line of reasoning, managers who choose to diversify their holdings are cowardly benchmark huggers who are diluting their alpha for the sake of career longevity.

Many institutional allocators—and fund managers—believe in these principles. Followers of the Yale model in particular seem to strongly prefer public equity managers who follow this approach.

We have spent much of this summer evaluating the evidence for and against highly concentrated equity managers. In addition to reviewing academic and practitioner research (we particularly recommend this excellent piece by Owen Lamont), we set up a simulation environment to better understand the impact of concentration on portfolio returns.

Our simulations led us to a few simple conclusions. First, extreme concentration increases risk and decreases expected return. Second, the core task of investing is making predictions about the future. Neither doing more work nor having higher conviction leads to better predictive accuracy. Third, allocators to concentrated portfolios face a greater risk from survivorship bias in manager selection. We discuss each conclusion in detail below.

Extreme Concentration Increases Risk and Decreases Expected Return

The most important thing to understand about highly concentrated portfolios is the relationship between concentration and volatility. And volatility has a direct negative impact on returns through a phenomenon called volatility drag. To understand volatility drag, consider this: a portfolio that is down 10% in year one and up 10% in year two has lost 1% of value, a portfolio down 20% and then up 20% has lost 4% of value, and a portfolio down 30% and up 30% has lost 9%. Linear changes in volatility drive squared losses in total return. These extreme swings are more likely to occur in hyper-concentrated portfolios. Diversification is an easy path to reducing idiosyncratic risk.

The argument that managers should leave diversification to allocators misses the fact that volatility drag affects each concentrated manager alike. So even if manager strategies are uncorrelated, their individual expected returns are lower by the very act of their hyper-concentration. As a result, endowments and foundations are significantly more likely to fall short of the return thresholds they require to sustain distributions when they allocate to hyper-concentrated managers, as we demonstrate below.

The probability of return shortfall is a real measure of risk that matters even to patient investors who can ride out drawdowns and bear volatility. If a foundation is required to pay out 5% of its assets every year, it needs to generate an annualized portfolio return above 5%, net of fees, in order avoid a shrinking asset base over time. Falling short of this threshold over a long horizon, such as 10 years, represents a material loss of capital that would curtail a foundation’s ability to fund its mission in the future.

We can estimate this probability of shortfall by simulating the returns of manager strategies at varying levels of concentration. Based on data of US stocks from S&P Capital IQ, we simulated 10,000 manager portfolios at levels of concentration that ranged from 5 stocks to 500 stocks. Every manager in the simulation invests their portfolio with annual rebalancing over a 10-year horizon. This setup fully avoids survivorship bias as no manager drops out of the simulated database. We assumed that all simulated managers charge active hedge fund fees consisting of a 1.5% management fee and 20% carry, above an 8% annual preferred return, subject to a high-water mark. For liquidity purposes, we set the minimum market capitalization of holdings at $300 million. After simulating the net annualized returns over 10 years for all 10,000 managers at each level of concentration, we measured the probability of shortfall as the percentage of 10-year outcomes that fall below a 5% net annualized return. The figure below shows our results.

Figure 1: Probability of <5% Net Annualized Return over 10 Years (1996–2023)

Sources: S&P Capital IQ and Verdad research

The unranked portfolios show the effects of concentration alone, as holdings are selected at random without any factor tilts. The quality-ranked portfolios show the effects of concentration when combined with a ranking system where simulated managers select their best ideas according to profitability and free cash flow generation. These quality portfolios are formed from a universe that is ranked with 50% weight on Gross Profit/Assets and 50% weight on Free Cash Flow/Assets.

The unranked portfolios show that hyper-concentration doubles a manager’s risk of falling short of their LPs’ 5% minimum return target over 10 years. Portfolios of 5–10 stocks have a ~40% chance of returning less than 5% annualized over 10 years, whereas the shortfall risk for unranked portfolios with more than 50 stocks is roughly 20%. It’s important to note that the probability of shortfall begins to stabilize at around 50 stocks and remains about the same, all the way out to 500 stocks.

Quality ranking offers further risk-reduction benefits to diversified portfolios, with the probability of shortfall being 8–13 percentage points lower among quality portfolios with more than 50 stocks. However, the benefits of quality exposure do not show up in hyper-concentrated portfolios on average, as 5–10 quality stocks have about the same risk as unranked portfolios of the same concentration, at around 40% probability of shortfall.

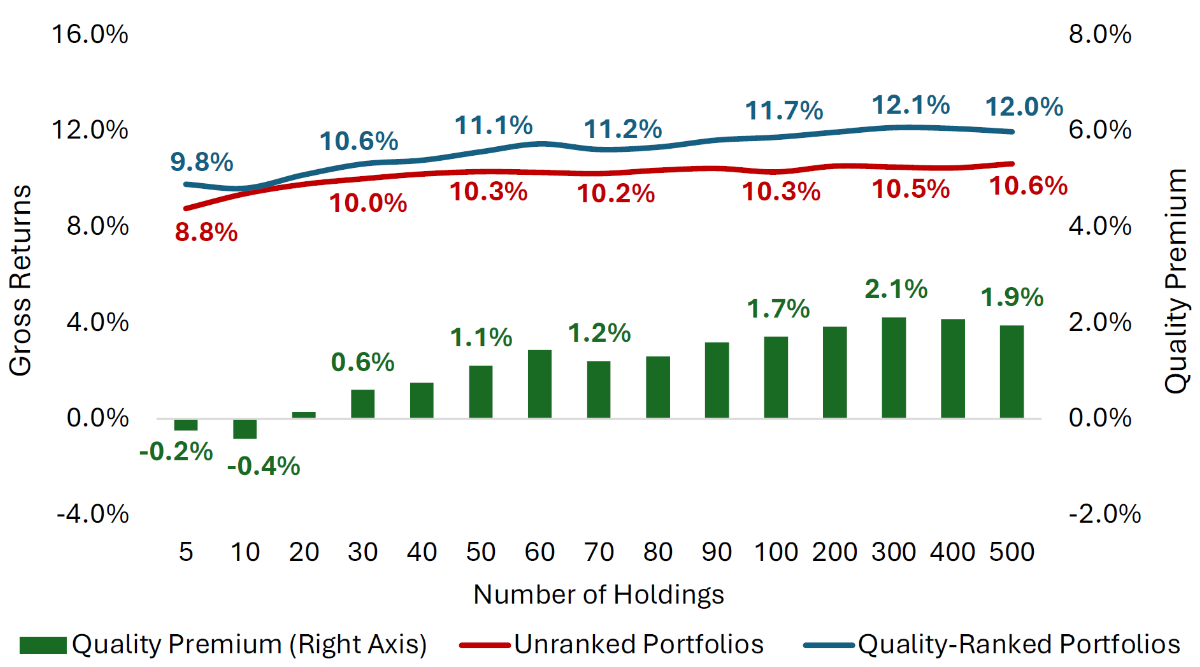

The reason for this is because volatility drag offsets the return premium from factor exposure, as shown in the figure below. Hyper-concentrated portfolios comprising 5–10 of the highest-ranked stocks actually have lower gross returns than diversified portfolios of 50 or more stocks. This is evident among unranked portfolios, where hyper-concentrated strategies of 5–10 stocks trail diversified portfolios by more than a percentage point, on average. It is also true among ranked portfolios, where hyper-concentrated quality strategies underperform diversified quality portfolios by 1–2 percentage points, even though the hyper-concentrated portfolios consistently rebalance into higher-ranked stocks than the diversified portfolios.

When we measure the quality premium—defined as the excess gross return of the quality-ranked portfolios relative to the 10% market return—we find that volatility drag more than offsets the benefits of quality exposure among hyper-concentrated portfolios. Despite being high quality, these hyper-concentrated portfolios underperform the market on average. On the other hand, diversified portfolios of quality-ranked stocks outperform the market by 1–2 percentage points on average, and this premium reliably exceeds 1 percentage point after portfolios hold more than 50 companies.

Figure 2: Gross Returns (Left Axis) and Quality Premium over 10 Years (1996–2023)

Sources: S&P Capital IQ and Verdad research. Returns reflect the median of simulated outcomes.

The bad news for hyper-concentrated portfolios gets worse after we account for fees, as shown in the chart below. Hyper-concentrated portfolios trail their diversified peers by 1.5–2.5 percentage points, on average. Once again, expected returns begin to stabilize after a diversification level of at least 50 stocks, with quality-ranked diversified strategies returning 8–9% net of fees and unranked diversified portfolios returning around 7.5% net of fees, on average.

Figure 3: Net Annualized Returns over 10 Years (1996–2023)

Sources: S&P Capital IQ and Verdad research. Returns reflect the median of simulated outcomes.

Evidently, diversified portfolios outperform their hyper-concentrated peers, on average. However, all of the median net return outcomes in our 10-year simulations fall below the 10% annualized return earned by the market. This finding is consistent with Fama and French’s research showing that the average active manager has negative alpha after fees.

Leaving diversification to the allocators, as the Concentration Manifesto argues, would leave the allocator stuck with a diversified array of excessively volatile, underperforming managers.

The Core Task of Investing Is Making Predictions About the Future. Neither Doing More Work nor Having Higher Conviction Leads to Better Predictive Accuracy.

Phil Tetlock’s famous book Expert Political Judgment showed that experts are no better than non-experts at making predictions about the future, even in their core knowledge areas. The biggest difference between the two groups was a much higher degree of conviction among experts that their forecasts were accurate—a self-confidence not merited by the empirical results.

The Concentration Manifesto’s argument for the importance of applying scarce mental capital to a small subset of stocks fails to account for the separation between an understanding of current events and the ability to predict future events. This illusion of control is best articulated in Buffett’s assertion that if you simply own a portfolio of three wonderful businesses that you fully understand, “bad things aren’t going to happen to those three.” Because no human being can predict the future, it is an illusion to believe that a complete and thorough understanding of a company’s latest earnings report serves as a guarantee against negative future surprises. In our view, it’s much more important to understand the statistics on the persistence and predictability of growth, something we’ve spent years researching and describing in our weekly research (see here, here, and here). As Owen Lamont so beautifully noted regarding the limits of human control, “you can only control what stocks you buy; a cruel and unforgiving world controls what happens next.”

We considered how much skill is required to outperform the market by 1% per year by comparing the difference between a threshold of 1% outperformance of the market and the median outcomes of our net return simulations by concentration. This difference gave us an estimate of the minimum value-add an active manager would need to provide for their strategy to return more than 1% above the market, net of fees. We also estimated the number of research hours per name, per quarter, possible at each concentration level.

Figure 4: Skill Required for 1% Net Alpha vs. Market (Left Axis) and Hours per Holding (1996–2023)

Sources: S&P Capital IQ and Verdad research. Returns reflect the median of simulated outcomes.

As demonstrated above, hyper-concentrated portfolios of 5–10 holdings require around five percentage points of value-add from their manager to beat the market by at least 1% annualized. On the other hand, diversified portfolios with more than 50 holdings place less burden on a manager’s skill, requiring 3–4 percentage points of value-add in order to outperform the market by 1% annualized. Factor exposure from quality ranking lightens the skill burden further to only 2–3 percentage points of value-add required for outperformance, among diversified portfolios.

A key argument by proponents of hyper-concentration is that fewer holdings enable a portfolio manager to allocate more research time to each company. This simple mathematical reality is clearly shown in the chart above. However, as noted earlier, there is a separation between full understanding of a business and control over what happens to that firm in the future (especially as a minority holder of public equity). And, like other economic systems, the relationship between understanding and hours of research is likely to be subject to the Law of Diminishing Returns, with smaller incremental gains in understanding after a certain threshold of research time.

Allocators to Concentrated Portfolios Face a Greater Risk from Survivorship Bias in Manager Selection

Based on the empirical evidence in favor of diversification, one may wonder why hyper-concentration has gained any appeal at all. Aside from the reality that one of the biggest proponents of hyper-concentration is also perhaps the world’s most successful investor, we believe another contributor to the concentration narrative is survivorship bias.

Hyper-concentration mechanically increases dispersion, resulting in eye-popping returns and headlines for the luckiest winners, while the unlucky losers quietly go out of business. As an example of this extreme dispersion among 5-stock portfolios, the spread between 5th and 95th percentile net return outcomes in our simulations is 19–20 percentage points. For context, this is double the 9–11 percentage points of dispersion among diversified portfolios.

Figure 5: Dispersion of Net Annualized Returns over 10 Years (1996–2023)

Sources: S&P Capital IQ and Verdad research.

Specifically, around 500 of our 10,000 simulated hyper-concentrated managers randomly earned net returns above 15% annualized over 10 years, while the bottom 500 simulated managers returned below -4% annualized, net of fees, over a decade. In the real world, the lucky top 5% of managers would be showered with positive headlines and publicity, as fundraising is positively correlated with past performance. On the other hand, the unlucky bottom 5% of real managers would likely close their funds as quietly as possible, resulting in survivorship bias.

The real-world outcomes of actual fund managers show results in line with the conclusions from our simulations. A mutual fund study by Sapp and Yan (2008) carefully avoids survivorship bias by including all US equity mutual funds that exist in the CRSP and WRDS databases from 1984 to 2002. Based on this comprehensive data, the authors measure outcomes for mutual fund managers at varying levels of concentration. Their main results are summarized in the table below.

Figure 6: Outcomes of US Mutual Funds by Portfolio Concentration (1984–2002)

Source: Sapp and Yan (2008)

We believe the results for three-factor alphas (which control for market, size, and value exposure) and fund death rates (which represent closed or liquidated funds) are of particular importance. Similar to the simulations we shared previously, the data on actual mutual funds shows that concentrated portfolios have worse outcomes on average. In the most concentrated category of mutual funds, three-factor alphas are reliably negative on average. Also, death rates are higher among the most concentrated portfolios, averaging around 38% probability of fund closure. This broadly corresponds with the ~40% probability of shortfall we estimated from the most concentrated strategies in our simulations. Most spectacularly, the highly concentrated mutual funds are roughly 2-3x more likely to die a quick and violent death, as shown by the acquisitions and liquidations that occur within three years of fund launch.

Conclusion

Based on the evidence from logic, math, and historical data, we believe the benefits of diversification stand on their own merits. And when the outcomes of diversified portfolios are compared against their hyper-concentrated peers, free from survivorship bias, it seems the case for diversification is self-evident. Light is perceived most brightly in the darkness, and the virtue of humility is recognized most clearly when contrasted against inordinate self-confidence. We believe investors who accept the limits of human clairvoyance are in the best position to capture the free benefits of diversification. In an uncertain world, we believe a humble embrace of diversification offers the more reliable path toward building long-term wealth.