The Calm Before the Storm

The benign credit environment may be temporary.

In a 2023 paper titled “Reflexivity in Credit Markets,” Robin Greenwood, Sam Hanson (who we should note is a valued adviser to Verdad) and Lawrence Jin review a set of new facts documented by academics studying the credit cycle over the past decade. Among them: “High credit growth is associated with both a higher probability of a future financial crisis and lower future GDP growth,” “periods of elevated corporate credit growth and low average borrower credit quality forecast low returns to credit,” and “the combination of large credit expansions and asset price booms predict financial crises.”

The paper adds to this existing set of facts about the credit cycle by setting out a behavioral model of the credit cycle that includes “reflexivity,” the idea made famous by George Soros that “distorted views can influence the situation to which they relate because false views lead to inappropriate actions.” In this case, those false views are held by investors who believe that low past defaults will always predict continued low defaults in the future. The inappropriate action is the continued provision of credit, which in turn allows struggling and risky firms to delay default.

In the near term, in our view, these beliefs are false, optimistic and self-fulfilling: easy credit means default rates remain low. This leads to two dynamics in credit markets that are observed in historical data: “the calm before the storm” followed by “default spiral” episodes. Credit spreads are often low before a crisis and then rise unexpectedly and rapidly. As the authors explain, “under-priced credit eventually induces firms to become highly leveraged, making them more vulnerable to adverse fundamental shocks and thus raising the likelihood of default over the longer run.”

Supporting evidence for this behavioral view of the credit cycle comes from a set of factors that negatively predict excess return on high-yield bonds. The factors are the “high yield share,” or the percentage of corporate bond issuance that is high yield, the growth rate in outstanding corporate credit, easy bank lending standards, and tight credit spreads that contain little compensation for default risk.

These measures rely on data from the high-yield bond market beginning as early as 1983. Indeed, for researchers interested high yield, the historical dataset is now long and rich, containing forty years of high-quality data. Looking at the high-yield bond market in isolation, there is not a lot to worry about today. High-yield debt has grown but not in any sort of dramatic fashion, as can be seen in the chart below.

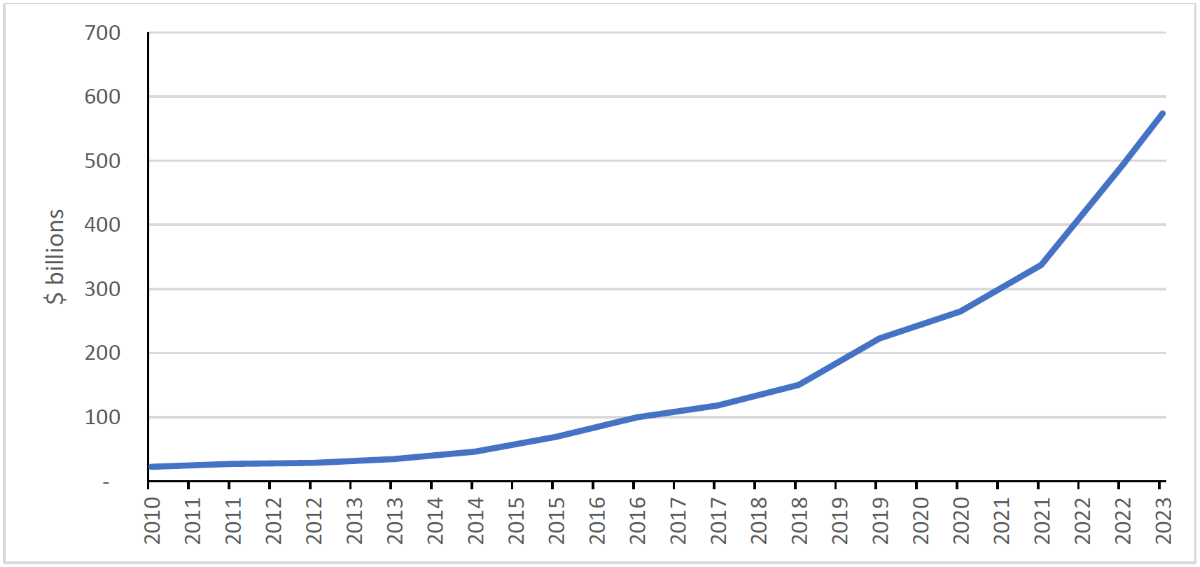

Figure 1: High-Yield Market Value

Source: Bloomberg

In fact, in high yield, the only factor that could be argued to be at concerning levels is the level of credit spreads, which are quite tight by historical standards. The ICE BofA high-yield spread tracked by the St. Louis Fed is now at just 3.1%, a level that is in the lowest 9% of spread readings since 1996. But other measures of health are less concerning. Low-quality issuance has been subdued, overall high-yield bond growth has been reasonable, and lending standards have not been overly loose.

The story is not the same in direct lending, which has featured rapid growth in low-quality credit. In 2010, high-yield bonds had a market value of $930 billion while, according to a 2024 FEDS Notes, direct lending had just $22.5 billion of invested capital. It was 2% of the size of the high-yield market. By June of 2023, direct lending had grown to $574 billion or 46% the size of the $1.25 trillion high-yield market. Note that we cite invested direct lending capital as we believe it is most comparable to high yield. The broad private credit market is much larger and grew from $200 billion to $1.2 trillion over the same period, making it almost equal to the high-yield market.

Figure 2: Direct Lending Invested Capital

Source: Preqin via The Federal Reserve FEDS NOTES

In direct lending, the only factor that could be argued not to be concerning is the spread, which has been relatively high. In our opinion, this high spread is necessary compensation for riskier lending, as we have argued before. But the more important observation today is that the high yield share of credit issuance is quickly rising because almost all direct lending issuance is high yield. The absolute volume of credit growth is also obviously high, and while we have no direct measure of lending standards, our assumption is that they are loose enough to have successfully won over volume from the leveraged loan market.

We believe that the false view held in this case is that the past returns of private credit will continue. High past returns have driven inflows into the asset class, which has benefited performance. As with credit markets in the past, continued inflows can refinance problems and allow investors to earn the high coupons for a while. But, as we showed in Yield is Not Return, higher yields are often associated with lower returns over time.

In our view, neither private credit nor direct lending have rewritten the rules of credit risk. We’d argue that what passes for innovation in finance is often just repackaging risk in more convenient and higher-fee wrappers. To cite just one example of risky lending that grew rapidly, faced a reckoning and then developed into a more stable, mature market, look no further than high yield. The junk bond boom of the 1980s was built on the idea that the historical performance of high-yield bonds more than compensated for their higher risk. At its core, this idea has proved to be correct, but it was taken to extremes. After the boom in the 1980s, the Moody’s below–investment grade default rate hit 6% starting in 1989 and spiked to 10.4% and 9.1% in 1990 and 1991. But what developed afterwards was a mature market that is now tame compared with its history. We suspect that private credit will follow a similar path.