The Banking Crisis

Is the US economy at risk of a Minsky Moment?

Growth is the primary objective of most corporate CEOs. For most businesses, growth requires innovation, investment, and excellent execution. It’s difficult to grow rapidly, so fast-growing companies often garner premium valuations and industry accolades.

But there’s one industry in which rapid growth is easy: banking. Want to quickly grow a bank? Start extending credit at lower rates to less creditworthy borrowers, and rapid growth will follow. Not having a chief risk officer can help facilitate this expansion. The shareholders of your rapidly growing bank will usually be pleased. At least in the short term.

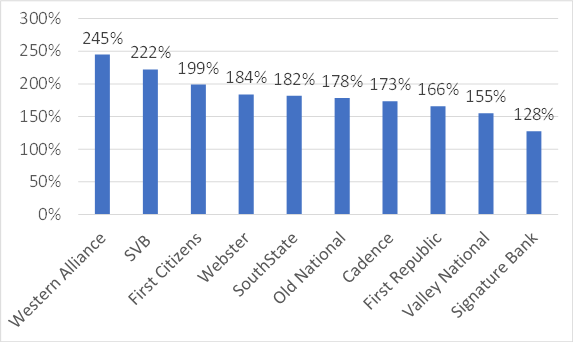

However, the problems typically start to surface when the loans need to be repaid. Academic research has shown that the stocks of banks in the fastest quartile of loan growth underperform those of banks in the slowest quartile of loan growth by 12 percentage points over the subsequent three years. The fastest-growing banks also have a significantly higher risk of failure. The below chart shows the publicly listed US banks with at least $10 billion in loans in 2017 that have had the fastest loan growth over the past five years.

Figure 1: Banks with the Highest Net Loan Growth (2017–2022)

Source: Capital IQ. Note: Includes all US banks with more than $10 billion of net loans in 2017. Includes banks that grew through acquisition.

Both of the banks that failed in early March (Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank) are on this top 10 list. And several others on this list—most notably First Republic and Western Alliance—have seen precipitous declines in their share prices in recent weeks.

But what precipitated SVB’s failure wasn't concerns about credit losses on its loans. Instead, SVB failed due to a devastating bank run that was triggered by concerns about the mark-to-market losses on its large portfolio of long-term US Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities.

Bank investors had recognized the problems at SVB and several of its rapidly growing peers for months. It’s not complicated. SVB had tripled in size since 2019, taking in loads of uninsured deposits from venture-backed startups during the heady days of late 2020 and 2021. SVB used those deposits to invest in long-term bonds at rock-bottom yields. The prices of long-term bonds decline when interest rates rise. And interest rates have risen in the past year. By a lot, in our opinion.

The share prices of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank peaked at the end of 2021, with both declining over 60% in 2022. In fact, the Wall Street Journal wrote an article in November 2022 pointing out the mark-to-market losses on SVB’s securities portfolio exceeded the value of its book equity in the third quarter of 2022.

But, while investors were slightly concerned, they were far from alarmed. Investors were mainly talking about banks’ rising net interest margins. They assumed that banks’ uninsured deposits would remain “sticky,” providing them with cheap funding that would allow them to “earn their way out” of these securities losses in a higher rate environment.

But in March, the market’s collective attitude went from yawn to yikes. All of a sudden, on Wednesday, March 8, a number of prominent venture capitalists were tweeting up a storm and telling their portfolio companies to withdraw their cash from SVB. The portfolio companies complied en masse. Depositors withdrew more than $40 billion from SVB on Thursday, March 9 alone. SVB began the year with $175 billion of deposits. By Friday morning, SVB had received further withdrawal requests in excess of $100 billion, and it was closed by regulators before it could open for business. By almost any measure, this was the most rapid and devasting bank run in modern US history. It wasn’t a bank run. It was a bank sprint.

A problem in plain sight that seemed contained and knowable suddenly became a panic on little to no news. What changed wasn’t the facts but rather investors’ perceptions of those facts. Or maybe it is better to say that what changed was investors’ perceptions of how others perceived those facts. Indeed, as Diamond and Dybvig showed in their Nobel Prize-winning work on bank runs, if an uninsured depositor comes to expect that other depositors are likely to withdraw their funds, it’s irrelevant whether the bank’s balance sheet is healthy or not: the only rational response for that insured depositor is to rush to withdraw or risk being the one holding the bag at the time of the failure.

What should worry us most about this situation is the way in which Silicon Valley Bank might be a metonym for the broader US economy, which has experienced years of zero interest rates, rapid credit growth, and such an increase in risk tolerance that people were willing to put their life savings in things like CryptoKitties.

Recent research by our consulting economist Sam Hanson and his colleagues at Harvard’s famed behavioral economics group found that rapid growth in credit and the prices of risky assets have historically signaled elevated probabilities of a financial crisis. Updating their methodology, we found that the United States entered the “Red Zone” for a potential crisis at the end of 2020. Importantly, the economists noted that crises do not immediately follow bouts of rapid credit and asset price growth: there is a 13% probability of a crisis within one year of entering the “Red Zone,” but this rises to a 45% probability within three years. Repurposing Buffett’s metaphor, after a bout of naked swimming, it typically takes some time for the tide to go out and for the nudists to be revealed.

There’s been no shortage of warnings about potential bubbles in US technology stocks, private equity, private credit, and venture capital over the past few years. But markets have proved more resilient than doomsayers would have guessed. This is not abnormal: we noted in our study of the 1990s tech bubble that we believe the smartest financial minds called the bubble years early (Ray Dalio and Peter Lynch in 1995, Seth Klarman in 1996, and George Soros in 1997).

But valuations—like the stability of SVB’s deposit base—depend on confidence. And just as withdrawing funds from a bank undergoing a bank run is a rational though destructive act, so too is selling shares in overvalued and now declining securities. This meta-analytic, reflexive logic is the key driver of what Ben Bernanke deemed “the financial accelerator,” when financial markets themselves become the source of macroeconomic volatility due to the withdrawal of liquidity. Financial panics are, ultimately, crises of beliefs as Andrei Shleifer has argued.

We believe the key metric for tracking these risks is the high-yield spread. And we’ve seen tremendous volatility in the spread this year, with spreads falling sharply in January on good economic news then soaring after the Silicon Valley Bank failure. This elevated volatility is an indicator of investors’ unsettled psychology as they struggle with how to process a volatile macroeconomic environment. Today, we feel one salient frightening event away from a Minsky Moment.