Persistent Alpha

Lessons from the Pod Shops

By: Daniel Rasmussen, Chris Satterthwaite, & Lionel Smoler-Schatz

A new model has overtaken the hedge fund industry: the multi-strategy “pod shop” that features dozens of siloed manager teams. The financial news has been full of stories about both their fundraising success (Millennium recently raised another $10 billion) and their impressive investment returns (Citadel’s flagship multi-strategy fund has delivered annual returns of 19% since 1990).

These pod shops share a few distinctive features, as Giuseppe Paleologo, a former risk director at Millennium and Citadel, explained recently on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots Podcast. They manage a large number of teams (Millennium reportedly operates close to 300). Money is constantly being reallocated among the pods on a seemingly simple basis: alpha generation. “If they perform well, to give them more capital,” says Paleologo. “If they don't perform well, to take capital away from them or let them go.” The individual pods run with very little market and factor exposure, and remaining undesirable exposure is usually hedged out by a centralized risk team. These funds are run at very high leverage levels, amplifying the uncorrelated alpha return streams generated by individual PMs.

With these facts in mind, we had a simple idea. What if we took all the actively managed mutual funds and ETFs and treated each as its own pod, using our own internal risk model to separate the funds’ alpha from their systematic market and factor exposures? Could we build a sort of poor man’s pod shop—or at the very least use the exercise to better understand the model? We don’t think there’s any reason to think that Fidelity or Capital Group’s best managers aren’t equally skillful to Citadel’s or Millennium’s.

We know from decades of research from SPIVA that most active managers struggle to beat the market and that outperformance of the index is not persistent over the long run. Making pod shop lemonade out of the lemons of the world of active management must, therefore, rely on either shorter time horizons (perhaps active managers have hot streaks of a few months that we can bet on) or the risk model they use to manage and combine the streams is enormously powerful.

Short-Term Persistence of Alpha

We can test the first possibility empirically. We analyzed alpha persistence across 3,182 actively managed mutual funds and ETFs from 1997 to 2024. Using rolling time-series regressions of fund returns against 13 factor return streams, we estimated fund-level factor exposures (betas). These factor betas included market, value, size, momentum, and several others representing some of the most well-studied academic risk factors.

After estimating these exposures, we measured alpha, which represents a fund’s incremental performance unexplained by factor betas. As illustrated in Figure 1, alpha over any investment period was calculated as the total return (net of fees), minus the risk-free rate (Fed funds) and factor-implied performance. Factor-implied performance was derived by applying each fund’s beta coefficients to the actual realizations of each respective factor.

Figure 1: Illustration of Fund-Level Performance Attribution

Source: Verdad analysis. A fund’s return over any investment horizon is the sum of the risk-free rate (green), the factor-implied excess return (blue), and the residual return, or “alpha”(orange), which measures how much a fund outperforms or underperforms its factor exposures.

After estimating alpha and betas, we sorted funds into decile portfolios based on trailing 12-month alpha. For each equal-weight decile portfolio, we measured alpha generation over forward-looking 1-, 6-, and 12-month periods.

Importantly, positive alpha does not necessarily mean positive absolute returns. For instance, during a small-cap downturn, a small-cap-tilted fund that loses less than expected could still exhibit positive alpha. Similarly, a large-cap growth fund performing well but underperforming its expected returns would show negative alpha.

So does alpha persist? Consistent with prior academic research, we find strong evidence of short-term alpha persistence (1-12 months). Funds that recently outperformed their benchmarks tend to continue outperforming, while poor performers tend to continue lagging. However, beyond the 12-month mark, performance reverts to the mean and long-run alpha trends toward zero. Figure 2 shows the 1M, 6M, and 12M forward alpha by decile of historic alpha.

Figure 2: Annualized Forward Alpha for Historic Alpha-Sorted Deciles

Source: Verdad analysis. Deciles are formed daily based on trailing 12-month alpha. Alpha is calculated for each fund using beta estimates from time t.

These graphs suggest that alpha is not entirely random. Short-term alpha persistence (1-12 months) does appear to exist in the mutual fund and ETF universe. A strategy that constantly reallocates money to the highest alpha-generating funds with 1- to 12-month holds while systematically hedging risk exposures could potentially harvest significant alpha.

The Importance of Risk Models

Central to this strategy, however, is an all-important risk, or factor, model. As Paleologo explains, “A factor model is a little bit like having a market model on steroids.” The model must effectively capture all key drivers of risk to allow a firm to run with 5-10x leverage as multi-managers do. Inaccurate forecasts of volatility, correlation, or an overlooked risk factor could easily lead to a wipeout of capital.

These risk models must consider currency risk, region and sector exposures, style factors (e.g., size, value, momentum) and can even take into account topical thematic dimensions (e.g., COVID, GLP-1, “Trump trade”).

When well-constructed, a powerful risk model allows a firm to hedge out systematic risk (volatility), leaving only exposures to the desired alpha streams. Even small alphas can subsequently be transformed into high-return portfolios with enough cheap leverage.

Performance of the “Public Pod” Strategy

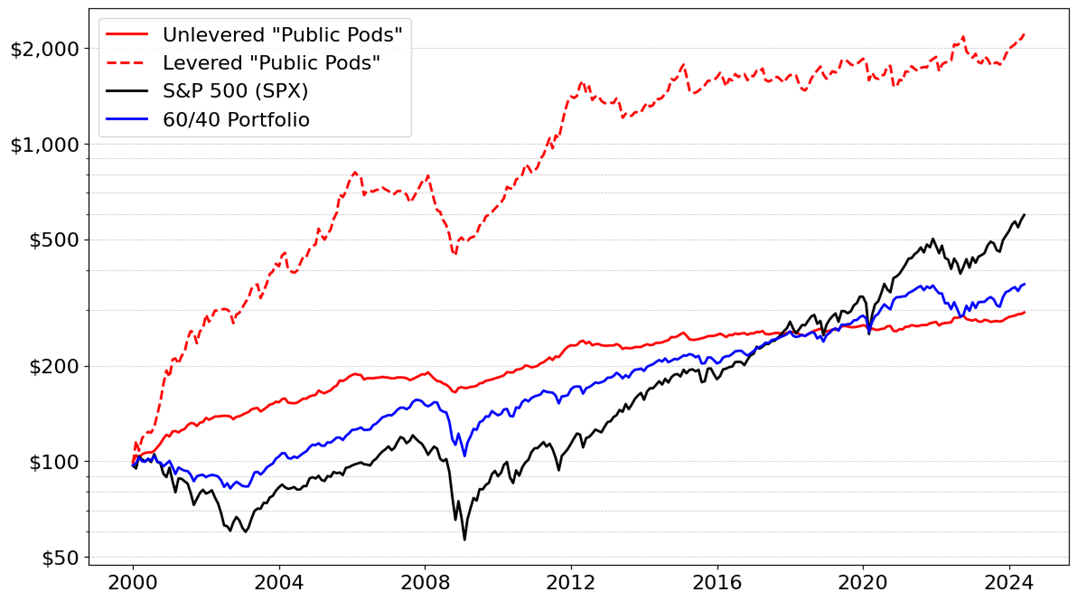

To illustrate this point, we simulated a “public pod shop” strategy, rebalancing monthly into the top 10% of funds ranked by trailing 12-month alpha. We also ran a levered version of this strategy, applying enough leverage to match the volatility of the S&P 500, which amounted to ~4x leverage. Figure 3 and Table 1 below show the performance of the levered and unlevered “Public Pods” approach against the S&P 500 and a 60/40 portfolio.

Figure 3: Simulated Performance of “Public Pods” Strategy

Source: Verdad analysis. The “Public Pods” portfolio rebalances into the top decile of alpha-producing funds each month based on trailing 12M alpha generation. The levered portfolio matches the annual standard deviation of the S&P 500 and assumes 1% net leverage cost per turn (at 4x leverage, this costs the strategy ~3% per year). The 60/40 is comprised of 60% weight to the ACWI and 40% to US 10Y Treasurys.

While the unlevered “Public Pods” portfolio generates lower absolute returns than the S&P 500, it achieves this with significantly less volatility due to its factor hedging, achieving an information ratio of 1. When combined with leverage, the portfolio outperforms the S&P handily with equivalent volatility and less extreme drawdowns.

We think it’s possible that the pod shops are succeeding not just because they have access to exceptional talent but because of their disciplined execution. It’s possible that their edge lies in dynamic capital allocation to short-term alpha generators, rigorous risk management using advanced risk models, and the strategic use of leverage to amplify returns. If those are indeed the core building blocks in the model, there’s no reason it couldn’t be reengineered using the thousands of public managers plying their trade in liquid funds.

Acknowledgments: Cees Armstrong and Marie Schaefers spent last summer assisting on this research. Cees is a junior at Stanford University majoring in math and computer science and minoring in classics. In his free time, he enjoys reading, watching football (soccer) and getting outdoors. He intends to work in either finance or technology both next summer and beyond. Marie Schaefers is a junior at Harvard College. She majors in economics with a minor in psychology and plays for Harvard’s varsity field hockey team. In her free time, Marie enjoys spending time outdoors and trying out new sports. With a keen interest in behavioral finance, Marie is excited to deepen her knowledge through her upcoming internship in Sales & Trading at Morgan Stanley next summer, where she will have the privilege of working for the amazing Mina Pell Mitby.