Death to the Lost Decade

In Search of a More Balanced Approach to Asset Allocation

Note: This is part 1 of a series on asset allocation. To download our full 50-page report, please click on the link at the bottom of this email.

An anonymous internet satirist created a mock table of contents for a new journal called The Journal of Rearview Mirror Portfolio Management. The first proposed paper is entitled “Endowment Performance: What You Should Have Done 10 Years Ago.”

The title is clever because it’s true. Many investment committees spend a disproportionate amount of time focused on the last decade, which, in addition to being the easiest time period to remember, is also the time period in which those on the committee were making decisions together. So the lessons of the last 10 years become conventional wisdom, only to be unlearned as—surprise!—macro economic conditions shift to reward an entirely different set of asset classes and asset allocation decisions.

We believe the foundations of good long-term investing must be built on a long-term study that incorporates many different market environments and seeks to make decisions that would have stood the test of time. Our focus on small-cap value equities is informed by this view: across many markets across long periods of time, equities have been the best performing asset class, and small-cap value stocks have outperformed broader equity indices.

But small-cap value stocks are a niche asset class, representing about 5% of equity market capitalization. So we have spent a significant amount of time thinking more broadly about diversification and timing. What is the right mix of asset classes, and how should that mix vary with economic conditions?

The last decade of experience would suggest that this project is largely a waste of time, that a simple 100% US equity portfolio or a classic domestically oriented 60/40 portfolio represent the peak performance and peak Sharpe ratio available, that there’s no better way to improve long-term returns than increasing your equity allocation, and that bonds provide sufficient diversification for those investors more focused on Sharpe ratios. But the last decade of experience was also the decade that delivered the best Sharpe ratio for investors holding a traditional 60/40 portfolio in 60 years.

Figure 1: 10-Year Rolling Sharpe Ratio for the 60/40 Portfolio Since 1900

Source: Goldman Sachs Balance Bear Repair, July 21, 2020

Stable growth and tame inflation rewarded both equities and bonds and rendered less valuable any diversifying assets that sought to profit from more volatile or negative growth or higher inflation. Macro-economic analysis—and even more simple concepts like international diversification or value investing—failed to benefit investors.

But growth has not always been so stable nor inflation so tame. And when those key economic drivers have behaved differently, the results for investors in different asset classes have been markedly different. Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio said that investors should worry primarily about two big economic variables: the rate of economic growth and the rate of inflation. “I knew which shifts in the economic environment caused asset classes to move around, and I knew that those relationships had remained essentially the same for hundreds of years. There were only two big forces to worry about: growth and inflation,” he said.

According to Dalio’s framework, there are four macro-economic conditions investors should be prepared to deal with: rising growth and falling inflation, rising growth and rising inflation, falling growth and rising inflation, and falling growth and falling inflation. This framework divides US market history into four quadrants based on whether the rate of inflation is increasing or decreasing and whether the rate of GDP growth is increasing or decreasing, as shown in the chart below. A number of firms have done work on this framework, and we have relied particularly on the thinking of Bridgewater and Hedgeye.

Figure 2: Average Conditions in the Four Quadrants (1955–2020)

Source: Bridgewater, J.P. Morgan, Hedgeye Research, Verdad

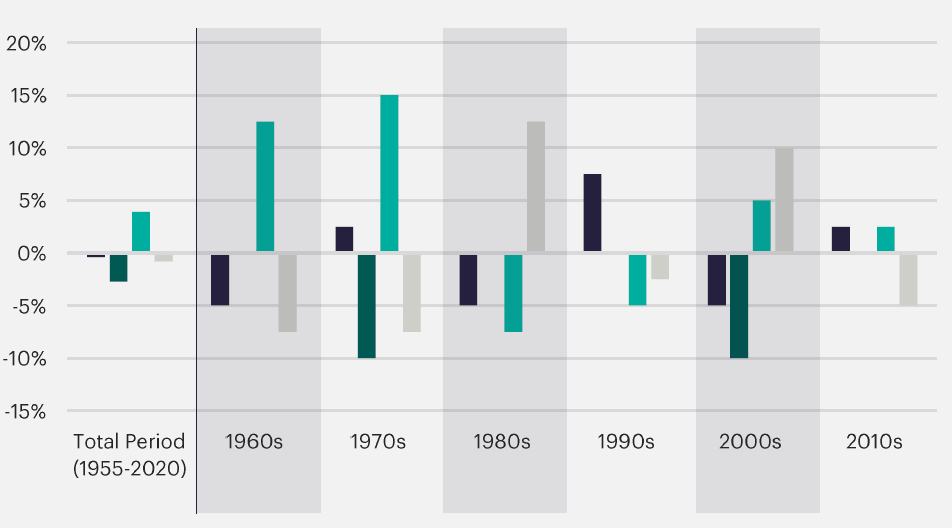

We can look back over time and see how these different economic conditions have predominated at different times in recent US history. These periods are defined in hindsight, according to the most recent revisions, and are thus useful for understanding the past but would not have been useful as trading signals at the time. The economy was in each quadrant roughly 25% of the time over the full period. In the chart below, we show how economic conditions varied relative to that level in each decade.

Figure 3: Quadrant Distribution Deviation From 25% by Decade

Source: Verdad

During the 1960s and 1970s, the US economy saw choppy real GDP growth and significant inflation, with quadrant 3 (falling growth, rising inflation) being the most prevalent condition. The 1980s and the 2000s both experienced two significant recessions, so quadrant 4 (falling growth, falling inflation) was disproportionately prevalent. The 1990s and 2010s had relatively balanced distributions of quadrants, with strong growth and limited inflation.

These different economic conditions rewarded different styles of investing, with significant differences in which asset classes performed well or poorly. The chart below provides a visualization of which asset classes performed best in each of the macro-economic conditions. Assets that cross quadrant lines performed well across the conditions.

Figure 4: Asset Performance by Quadrant

Source: Bloomberg, FRED, Ken French Data Library, GFD, Verdad. *Dow Jones REIT Total Return Index since 1990 used as proxy for REITs.

Recent history has us most familiar with what works in quadrant 1 (rising growth, falling inflation), with strong returns from both equities and corporate fixed income. But investors might be less familiar with what works in other economic environments. In periods of falling growth and falling inflation (quadrant 4), which we can think of as recessionary environments, US treasuries have historically provided the best defense against the combination of falling growth and deflation. And in periods of rising inflation, gold and oil are top performers. In Exhibit 1 on the following page, we show returns of each asset class in each of these economic environments.

Classic 60/40 portfolios, and more equity-biased asset allocation models like the Endowment Model, tend to be significantly under-allocated both to US treasuries and to commodities. And investment strategies, like risk parity, that incorporate this four-quadrant framework therefore tend to place a larger emphasis on treasuries and commodities and their strategic use in reducing risk from unexpected inflation or economic recessions.