Bank Run

Understanding the causes of the Silicon Valley Bank failure

By: Eddie Duszlak

This is a guest post by Eddie Duszlak, who runs a systematic, market-neutral hedge fund focused on small-cap banks. He previously wrote a Verdad Weekly Research about quantitative models for investing in banks, and we thought he was best positioned to share thoughts on the Silicon Valley Bank failure.

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank – and the crisis facing the banking industry today – started with COVID. After the U.S. government launched its stimulus program in response to COVID in 2020, the 1-year growth in deposits at U.S. banks increased at an unprecedented rate. The chart below shows just what an outlier this represented in the context of the last forty years.

Figure 1: 1-Year Growth in Deposits at FDIC-Insured Banks

Source: FDIC. Data is as of December 31, 2022.

It takes time for banks to originate loans, and banks were unable to put these deposits to work for them in such a short period. So banks broadly increased their securities portfolios, buying Treasury securities, mortgage-backed securities, and other rate-sensitive assets seeking to earn a yield. The 1-year growth rate in securities portfolios for FDIC-insured banks as of the end of the fourth quarter of 2020 was 21.4%, the fastest growth rate in forty years of data.

Typically, deposits and loans have historically tracked each other quite closely. The lines in the chart below are almost indistinguishable through 2008, after which they diverge. At the risk of oversimplifying, loan demand in the U.S. weakened after the 2008 crisis, and banks increased securities portfolios as a result. This growth in securities portfolios saw another acceleration in 2020 and 2021, as deposit growth spiked. Prior to this recent outlier period, it is noteworthy how little the slope of the lines varied over forty years.

Figure 2: Deposits and Total Loans & Leases

Source: FDIC. Values are in millions of USD. Data is as of December 31, 2022.

Here is where banks ran into a problem. The Fed hiked interest rates at one of the fastest paces in history, raising its benchmark rate from a range of 0.00-0.25% at the start of 2022 to a current target of 4.50-4.75%. As interest rates rise, bonds decline in price, and this has led to unrealized losses on banks’ securities portfolios. These unrealized losses are unprecedented in a historical context, driven by 1) the increased share that securities portfolios make up as a percent of banks’ assets and 2) the rise in interest rates being so rapid relative to history in response to U.S. inflation. The side effect of this rise in rates is also that depositors suddenly could get higher yields in other places, and deposit growth has turned negative recently as a result.

And this problem has not been solved by the Federal Reserve’s intervention this weekend. The losses on these securities portfolios are unrealized. The issue arises if a bank is forced to realize these losses. This is essentially what happens during a bank run. As depositors take their funds from a bank, part of that bank’s funding goes away, forcing them to sell assets. It is the opposite of how banks increased securities portfolios when deposits surged. These same banks would be forced to sell securities if deposits flee, causing the unrealized losses to become realized and creating a need for capital. This asset-liability mis-match, where long-dated assets are funded with short-dated liabilities, is not unique to SVB but it is how a bank works.

There are many out there writing SVB off as an isolated incident – that it was different from most banks, given its focus on the tech sector and the above average percent of funds that were not FDIC-insured. To be clear, these are both fair points. SVB was different. SVB had a larger securities portfolio than most banks and a focus on a part of the economy that has faced headwinds in recent months. It also did, as a result of focusing on businesses, have more uninsured funds.

SVB is not the only bank to have losses in its securities portfolios though. There are numerous other banks in a similar situation, where accumulated other comprehensive income (“AOCI”) is negative due to these unrealized losses and the losses are material relative to those banks’ total equity capital. While these banks are facing the prospect of bank runs that reduce their deposit funding base and force them to realize these losses, the stock prices of these banks are also experiencing sharp declines, which reduces their ability to raise funds from capital markets through share sales. This is a very challenging dynamic, but one which the comprehensive backstop of depositor funds by the Federal Reserve might forestall.

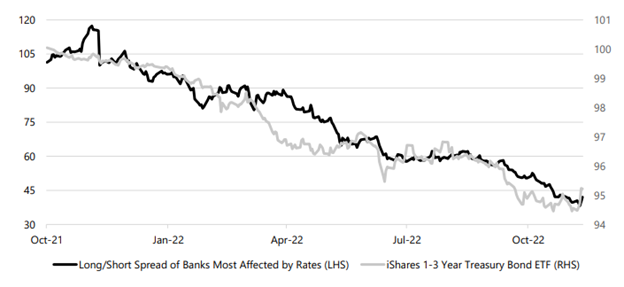

And we can see the market pricing this risk in the cross-section of banks. In 2022, there was significant dispersion between bank stocks that were most sensitive to rates due to losses on securities portfolios. This spread was largely driven by a stock’s correlation to the U.S. 2-year yield, a factor that had not really mattered in recent history previous to last year. With 2-year yields declining sharply over the last few days, the spread between banks most positively and negatively affected by rapidly rising 2-year yields could show signs of a reversal, as mark-to-market losses on securities portfolios reverse course and become mark-to-market gains. I created a proxy indicator for this spread using bank stocks that have been most impacted, positively and negatively, by the rapid rise in rates. This can be seen in the below chart.

Figure 3: Spread of Banks Most Affected by Rise in Rates

Source: Virtuent

It is noteworthy that three of the ten stocks with the strongest correlation to bonds last year have been shut down by regulators this year.

The irony is that, during this panic, the root cause of the problem has reversed sharply, as the U.S. 2-year Treasury yield has declined by 68 basis points since Wednesday of last week. For banks not facing deposit runs who have unrealized losses on securities portfolios, nobody is thinking about the prospect of mark-to-market gains due to a decline in interest rates. Of course, a decline in rates driven by the chaos experienced last week would point to larger problems, and this brings us to what is likely the topic everyone will be discussing in the coming months.

It would be shocking if we are not talking about loan-level delinquencies, charge-offs and credit losses later this year. Our expectation is that the stress banks’ asset-liability managers are under right now gets shifted to banks’ credit officers in the second half of this year. This is the slower-moving risk in banks that has been dormant for many years now thanks in part to easy monetary policy, and it seems to be awakening due to the knock-on effects of higher interest rates and the draining of liquidity from the financial system.