Shorting Credit

Short credit to get long credit

By: Greg Obenshain

On November 8, 2024, the high-yield spread hit 273 basis points, a level only breached for several months in 1997, one day in 1998, and for a few months in the beginning of 2007.

Figure 1: High-Yield Spread

Source: FRED, ICE BofA US High-Yield Index Option-Adjusted Spread

So today, we want to write about shorting credit. Let’s start with why shorting credit might be a horrible idea.

First, spreads can remain low for long periods of time, and market timing based on valuation is a dangerous game. A cursory look at the chart above will tell you that there have been perhaps six moments in a 28-year period when shorting credit worked well—often right before recessions. There have been plenty of periods where low spreads remained low or even ground tighter.

Second, individual bonds have mostly positive expected returns, with very few big losers. Given that bonds are a contract, over any reasonable period of time, few bonds should lose money. This is true even when spreads are low. Bonds generally have to default to cause permanent loss. By contrast, in equities, returns come from huge winners offsetting many large losers (but with losses capped at 100%). This is easiest to see in the chart below, which sorts equity and debt returns into percentiles each year and then takes the average of each percentile over the full period.

Figure 2: Distribution of Annual Equity Returns and Annual Debt Returns, 1997–2023

Source: Verdad Bond Database, Capital IQ. Companies with both equity and debt returns. Debt returns are weighted by outstanding debt. Y-axis truncated at +/- 80%.

On average, 39% of equities in this dataset have negative returns each year. Contrast this with debt, where only 15% of bonds have negative returns each year and only 5% of bonds have negative returns of greater than 10%. The base rate of success for shorting bonds is very poor.

And that base rate does not consider the cost of shorting. The cost of shorting debt is similar to that of shorting equity at around 1.25%. Some of that cost is the borrow fee, which for both equity and debt is around 0.25% (but can go much higher). The rest comes from the net interest spread between what you earn on collateral and what you borrow. In general, if you build a portfolio that is 130% long and 30% short, the 30% cash collateral for shorts earns Fed funds minus a spread, and the 30% you borrow to increase longs costs Fed funds plus a spread. Assuming 0.50% on each side, the net interest spread is around 1.0%.

For equity shorts, this cost is trivial. In the chart shown above, you’d make money 37% of the time rather than 39%, and 1.25% is small relative to most of the payoffs. The cost to short an equity is not going to change your decision. It's more consequential for bonds. In the chart above, you now make money 12% rather than 15% of the time, and 1.5% is a much larger portion of the payoffs.

The big difference between shorting equity and debt is dividend and interest payments. You will need to pay a dividend on your equity short only when the company declares it, but you must pay interest on your bond every single day. For those not familiar with bond trading, when you buy a bond, you might pay 98 cents on the dollar, but you add to your payment the accrued interest since the last coupon payment. The seller gets their interest right away. If you sell the bond at 98 cents on the dollar the next day, the buyer pays the 98 cents plus the accrued interest, which is now higher than the previous day by the coupon divided by 360 (corporate bonds accrue assuming a 360-day year). The consequence of this is that you bleed the accrued interest every day that you are short a bond.

This is why the most obvious things to short can be extremely dangerous and painful. We’ve long pointed out that low-quality credit underperforms high-quality credit. The chart below shows the annual returns by rating category versus the average yield for that rating category.

Figure 3: Returns vs. Yields by Rating Category

Source: Bloomberg

So why not just short low-quality bonds, like single B and CCC bonds? The problem is that the market is at least partially efficient and demands high yields from low-quality credit. You can see that it is very expensive to short low-quality bonds, which means that if you are going to do it, you’d best be right and be right quickly.

Shorting bonds as a market timing tool is probably a bad idea, and shorting low-quality credit is also probably a bad idea. So why short credit at all?

The reason to short credit is to reduce common risk factors and to ideally to add pure alpha to a portfolio.

The most common trade here is to short Treasurys against credit to reduce or eliminate duration risk. A more sophisticated way to do this is to short investment-grade credit bonds that the investor expects to deteriorate in credit quality against a portfolio of credit that is expected to improve in credit quality. The net effect is to allow the investor to increase exposure to the credit-improvement factor while reducing exposure to the Treasury factor. Importantly, the shorts are not adding return themselves (they are, in fact, likely to detract on a stand-alone basis), but they are transferring the source of return from duration to the credit-improvement factor. This is different than simply adding leverage because adding leverage just increases exposure to the credit longs and increases risk.

Increasing the portfolio size by using shorts increases the exposure to the spread between expected credit winners and credit losers. How beneficial that is depends both on the spread of performance between credit winners and credit losers and how it changes the risk of the portfolio. But, in contrast to simply adding leverage, there are more ways to win.

Let’s look at a tangible example of where shorting credit against a long portfolio could help. It has been widely noted that bonds that fall from investment grade to high yield subsequently outperform. Below we show the returns to the “Fallen Angel” bond index versus the high-yield index.

Figure 4: Fallen Angel vs. High-Yield Returns, 2005–2024

Source: Bloomberg, Verdad Analysis

We’ve separated the returns into their Treasury and credit (excess) component to make clear that most of the outperformance comes from the credit component. We’d really like to capture that extra return, but fallen angels come with an additional risk. Because the bonds were issued when the companies were investment grade, the duration of the bonds is higher. Currently, the average maturity of the Fallen Angel index is 7.1 years, versus 4.8 years for the high-yield index. Despite its higher overall credit quality than the high-yield index, the Fallen Angel index has higher volatility of returns, at 10% versus 9.2%.

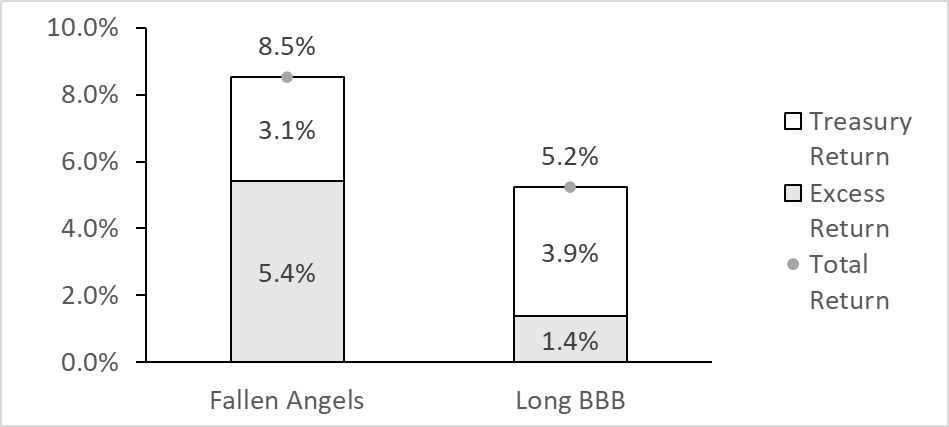

There is an obvious trade here, which is to short bonds in the BBB category that may be future fallen angels against the current fallen angels to both reduce duration risk and perhaps add credit return. This will result in a portfolio where the return is less dependent on the Treasury component and more dependent on relative credit performance. Below we show how fallen angels’ returns compared to long-dated BBB (> 10-year maturity) returns since the inception of the Fallen Angel index.

Figure 5: Fallen Angel vs. Long-Dated BBB Returns, 2005–2024

Source: Bloomberg, Verdad Analysis

This comparison glosses over important risk mismatches in the above trade, and we aren’t arguing to execute this as is. We are arguing that there is clearly enough raw material here with which to build a portfolio that is more than 100% long fallen angels and short long-dated BBBs in order to create a portfolio with a duration near or even below the high-yield index with higher exposure to the credit risk we want.

The point we want to drive home is that shorting credit can help increase factor exposure we like while controlling for the risks that we don’t want. Unlike in equity, where shorting can produce positive returns and therefore low net funds make sense, in credit you want to use shorting to transform factor risk and, in most cases, be fully invested. Credit returns are generally positive, and we want more exposure, not less. Shorting can provide an intelligent way to increase exposure to the credit factors we like and reduce exposure to risks we don’t.