Crisis Investing Part II: Predictability in Times of Crisis

This is the second in our series on crisis investing. To read the full 77-page report, click on the link at the end of this email.

Tolstoy wrote in Anna Karenina, “happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Markets are the opposite. Bull markets are all bullish in their own ways. The leaders in one expansion are almost never the leaders in the next. In the 2000s, companies with exposure to emerging markets and commodities were the biggest winners. In the 2010s, the FANG stocks and other technology companies drove the market expansion. It’s hard to predict what investors will fall in love with in a bull market.

But crises are alike. A recent academic study found that standard models for predicting returns in equity markets are 8x as predictive during recessions as during expansions. Take, for example, the classic factors that Nobel Prize winner Eugene Fama and his research partner Ken French developed: size, value, and investment. The smallest decile of stocks (SMB), the cheapest decile of stocks (HML), and the most conservative capital deployment decile of stocks (CMA) perform much better during crises and with much higher consistency than at other times. Figure 1 shows the average 2-year forward return starting in times of crisis (as defined by the high-yield spread rising above 6.5%) and Figure 2 shows the percentage of months during which the factor portfolio outperformed the broader stock market.

Figure 1: Avg 2-yr Return by Factor

Note: Returns are for an equal-weighted top decile portfolio of each factor. Source: Ken French Data Library

Figure 2: Months Factor Portfolio > Market

Source: Ken French data library

Crisis periods account for most of the excess returns attributable to each factor over the entire duration of our observed period, from 1953-2019.

The higher returns to quantitative investing accrue from the abnormally bad behavior of humans. During bad economic times, investors and lenders panic. Consider these quotes drawn from newspapers during previous crises:

“The main excesses of the past few years have scarcely begun to be liquidated.” – David L. Babson, Investment Advisor (1969)

“We’re talking about a possible economic wipeout.” – Tim Richardson, Editor (1986)

“They’re selling the good with the bad because they can. They’re throwing everything out the window.” – Brian Finnerty, C.E. Unterberg Towbin (2000)

This market sentiment has real-world impact. When investors and lenders panic, they reduce new lending and new investment as they attempt to de-risk their balance sheets.

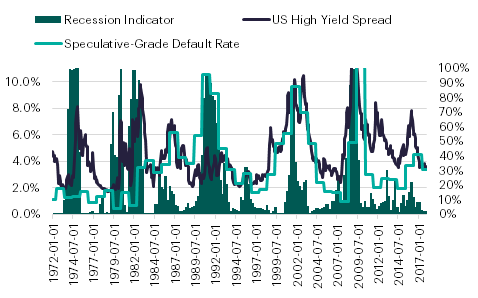

In a famous paper, Ben Bernanke labeled this the “financial accelerator”: economic shocks cause investors and lenders to panic and stop new lending and investing. Firms that rely on external financing reduce their discretionary spending, and weaker firms go bankrupt, all of which reflexively feeds back into aggregate economic activity. We can see this pattern recurring in the historical data. Below, we show default rates and borrowing costs for high-yield issuers compared to a GDP-based recession indicator.

Figure 3: Recessions, Borrowing Costs, and Default Rates

Source: FRED

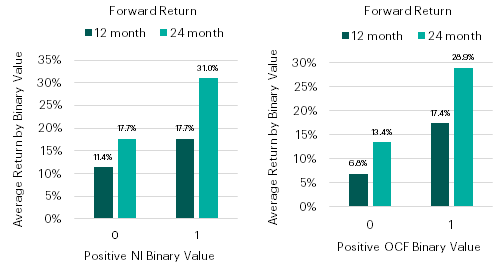

During recessions, the high-yield spread spikes upward and default rates soar. This stress rewards companies that are profitable and cash generative, while weak firms and companies that are investing heavily and burning cash struggle and often go bankrupt. We can see this in Figure 4 by comparing the performance of profitable and cash-generative firms to their unprofitable and cash-burning peers.

Figure 4: Returns for Profitable vs. Unprofitable Firms and Positive Cash Flow Firms vs. Negative Cash Flow Firms

Source: CRSP/Compustat

Simple, logical quantitative factors are significantly more predictive during these times of economic crisis than they are during expansions. Crises are high-stress environments where basic tests of solvency and profitability become seminally important in dictating a company’s survival and economic future. Companies like Tesla and WeWork may thrive during expansions when money is cheap, but such excesses do not long survive in times of market turmoil.

Investors who can keep their heads when everyone about them is losing theirs can therefore exploit simple predictable rules to make significantly outsized returns – and have the confidence that the probability of achieving these higher returns is much higher in times of crises than otherwise.

The only problem is the extreme behavioral difficulty of investing when others are panicking. For each crisis, we read through the newspapers at the time of the crisis and include key quotes from that research in this essay to help provide insight into just how stressed investors were – and the levels of fear one would need to overcome to profit.

In this paper we lay out the information you need to make decisions when crisis strikes. You can read the full paper by clicking on the link below. We will also share the key findings by asset class and within equities and bonds over the next few weeks in our weekly research.