Beyond Yield

How Upgrades and Downgrades Drive Bond Performance

By: Brian Chingono & Greg Obenshain

Many sophisticated investors believe fixed income—and corporate fixed income in particular—should have little to no role in investors’ portfolios. Some investors believe bonds are nothing more than a play on the unpredictable future direction of interest rates. Others despise bonds for their “negative skew,” arguing that the best you can do on a bond is earn the yield plus get your capital back, while the downside is default without recovery.

But we think these dismissals miss what is most interesting about corporate fixed income: the drivers of return over and above yield. It is simply not true that bonds only earn their yields, especially in higher yielding corporate credit. Changes in credit quality drive a meaningful spread in bond performance.

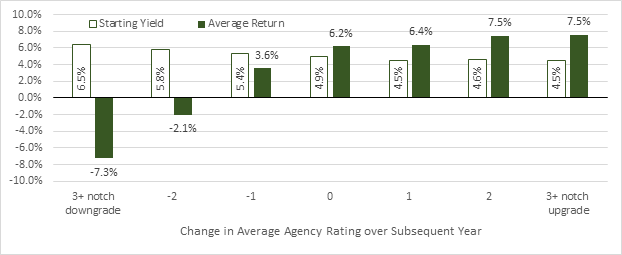

Active bond picking begins where yield ends: the central challenge of picking bonds is to select bonds that subsequently improve in quality and avoid bonds that get worse. One simple way to see this is to look at the performance of bonds that get upgraded versus downgraded by the rating agencies. The chart below shows the average starting yield and average subsequent 12-month return for BB bonds by upgrade and downgrade activity over the corresponding 12-month period.

Figure 1: BB Bond Starting Yield and Returns by Rating Upgrade and Downgrade, Oct 2015 – Oct 2020

Source: Verdad Debt Database

The money to be made in fixed income comes from buying bonds that subsequently improve, not from yield. The highest yielding bonds, especially B-rated and CCC-rated bonds are more prone to bankruptcy, and a singular focus on yield alone can lead to what we call the “fool’s yield” problem. Higher yields that look attractive can and often do result in lower returns.

Credit ratings are to fixed income what valuation multiples are to equities. Most credit analysts focus on yield and duration while most equity analysts focus on growth and discount rates, but in our view, the true drivers of return are changes in rating for bonds and changes in multiple for equities. We believe that the keys to the kingdom, in terms of understanding what truly drives credit returns, lie in understanding what drives change in ratings.

And while we respect the rating agencies more than most, the first step is to depart from agency ratings and define a more sensitive measure of changes in quality. Specifically, we use a market-implied rating derived from current market prices. Changes in this rating are an excellent measure of how the market is pricing the risk of the bond, and these changes provide a more precise target. When we switch to market-implied ratings, the magnitude of performance difference increases for ratings changes as shown below.

Figure 2: BB Bond Returns by Market-Implied Rating Changes, Oct 2015 – Oct 2020

Source: Verdad Debt Database

The key to getting the full value out of debt investing is targeting the segment of bonds that get better and avoiding the segment that get worse. To that end, we have spent the past year and a half studying how to use quantitative tools to assess the probability of upgrade and downgrade for corporate bonds. We built a massive database, we cleaned the data, we designed custom variables based on the factor literature, and then we ran linear regression and machine learning models to attempt to find the best strategy for predicting these changes in credit quality. This was a massive undertaking that required huge computing power and intense effort.

We believe this is a significant step forward in credit selection, and we look forward to sharing it with you. Next week we will share how we took on this problem, and in the week after that we will share what we learned and the outcomes of the effort.